While guiding the West Buttress slog up Denali, Nik Mirhashemi spotted a beautiful and direct line up the Southwest Face of Kahiltna Peak West that follows continuous ice runnels and chimneys.

On April 13th, he, Steven VanSickle, and I flew into a ghostly empty Kahiltna base camp. A few weeks later in the season, there would be a kerfuffle of seven summiters and moonies rigging up sleds or wallowing around waiting for a positive weather forecast, but there wasn’t a soul to be seen at that time. We stashed some extra gear and dragged sleds to an advanced base near Camp 1 of the main route up Denali. Because snow conditions were firm and the forecast was good for the next handful of days, we set out the next morning towards the face with loaded packs. The approach to the apron was straightforward and the schrund was filled in well so we crossed without issue. Steven volunteered to take the first block. The climbing was immediately high quality and difficult. Steven “VanMissile” efficiently zipped up the first pitches on the sharp end. We laughed to each other because the climbing was so great: “How has this gem in plain sight of the Denali congo line gone unattempted for so long?!”

Steven continued his block up another nice looking pitch, but it turned out to have a long stretch of unprotected climbing through its crux, which involved pulling over an overhung lip using sun rotted ice and bad feet on smooth slabby rock. While he made these moves, an ice patch fractured, sending Steven tumbling down the chimney. He ripped a bad screw out of the rotten ice before catching on a better one below. He fell about 20 pinballing meters down the chimney before catching at about the same level as I was belaying him from. It was one of the scariest things I’ve ever seen.

“I think my ankle is broken.”

We excavated a platform and lowered Steven onto it. When I unlaced his boot and started to explore, I immediately felt a big lump on the outside of his ankle that substantiated his suspicion. We considered our options and decided that we would request a helicopter as our first choice because assisted lowers and a sled drag would have been extremely painful and damaging to his injured limb. We texted TAT on the InReach who got in touch with parks service. Luckily, the perfectly clear skies and highly skilled rescue crew in the area allowed for Steven to be plucked into the air within a couple hours of the fall. They offered to take Nik and I too, but Steven said we should stay to get the gear from camp and try to do more climbing if we could.

Seeing a superhero like Steven take a big fall like that smacked the illusion of infallibility out of my mind. It hurts to live and then relive these experiences in memory, but as painful as it is to think about a bud getting hurt, I want to let these occurrences sear on the surface of my psyche as a sobering reminder that my partners and I are not tapped into magic and could be hurt or killed at any time. Climbing is amazing and worth some risk to me, but I I want to feel that fear because it keeps me on my toes, and hopefully makes me force some added security into these turbulent situations.

Nik and I somberly regrouped and descended. At the base of the route, I was surprised to hear him propose the option of getting back on the face. I had considered this before he brought it up but didn’t mention anything because I wasn’t willing to lead the pitch that Steven fell from. Nik said he would and I tried to reason that my hesitance to try it again was more emotional than logical since we wouldn’t have felt uneasy about trying another route of similar difficulty. We discussed it for a while and jokingly asked “What would Mark Westman do?”, so we stashed our packs and descended down the glacier to prepare for another attempt.

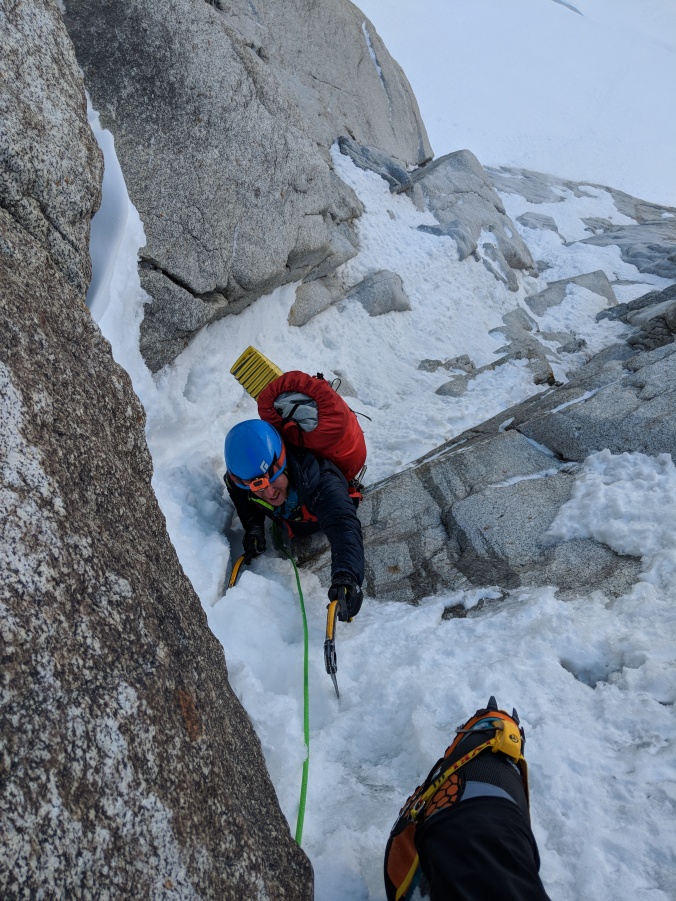

The next morning (is 2 a.m. morning yet?) we repeated the soul-aching alpine start, then slogged and climbed to our high point of the previous day. We decided that hauling the leader’s pack would be worthwhile for the hard climbing, so Nik clipped one rope and tagged the other. He cautiously pulled the difficult moves where Steven had fallen but managed ok with a few healthy grunts. He found that the ice above was too rotten to climb, but creatively managed to french-free a thin crack to the right and traverse back to the ice where it improved. A couple more fantastic pitches of ice chimneys put us on a massive snow ledge that splits the upper and lower headwalls. It was still early, so we brewed up and continued through the increasingly high-quality ice runnel system above. This amazing section of the climb was something like a longer harder version of Ames Ice Hose in Colorado. On the third pitch up the upper headwall, we traversed left to find a good ledge. At about 10 p.m., the Alaskan light was dimming fast, so we hacked a ledge out of the ice and set up camp for the night. We were able to fit nearly the whole tent onto our ledge, so we rested well.

Feeling refreshed the next morning, we jumped straight into a difficult leaning chimney that brought us back to the direct line that we had followed to this point. An involved ice pillar and some more chimneying put the hard climbing behind us. Once we reached the calf burning summit ice slope we took the ropes off and started huffing air. We reached the summit around 6 p.m. on our second day of climbing.

We had planned to descend by climbing down the col between Kahiltna West & East, then summiting Kahiltna East before heading down the non-technical mountaineering route of the South Ridge, but when we reached the col, we believed we could descend directly down to the south in relative safety, so we continued down with a handful of abalakov rappels and a bunch of down climbing. Some sarac exposure that we didn’t expect appeared once we were most of the way down the col, so I wouldn’t recommend this option for future parties. I think rappelling the route might be the best choice, even if that means spending another night out.